THE ORANGE NAVY – PART 4

Coronel and The Falklands

Imperial Germany was a latecomer to the scramble for empire which occupied european countries in the nineteenth century and, as a result, its colonial possessions were less than those of Britain, France and Russia, and even Portugal and Belgium seemed to have greater possessions.

The Far East and the Pacific Ocean was one area where Germany was able to acquire territory and subject peoples. By the outbreak of war in 1914 Germany had the Kia Chou area of China, the north-eastern part of New Guinea and the adjacent archipelago, and islands across the Pacific, including Bougainville, Nauru, the Marshalls, the Marianas, the Carolines, and Samoa. Only Kia Chou was heavily fortified, with a port and fortress being built at Tsing Tao. The islands were lightly held, mostly by local gendarmerie with German officers.

Germany had an East Asia Squadron composed of powerful and modern warships which was intended to provide the main defence for Germany’s Pacific empire. Its main base was at Tsingtao and, on the outbreak of war the main units in the Squadron were the Armoured Cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the Light Cruisers Dresden, Emden, Leipzig and Nürnberg. The Scharnhorst had a speed of 22.5 knots while the Gneisenau was a little quicker at 23.6 knots. Armament was identical for both ships, with eight 21cm guns, six 15cm guns, eighteen 8.8cm guns, and four 45cm torpedo tubes. The light cruisers were capable of a speed around 23 knots and they each had as armament ten 10.5cm guns. Emden and Dresden each had two 50cm torpedo tubes while those on the Leipzig and Nürnberg were 45cm.

This was certainly a mighty naval force but its effectiveness was greatly reduced by the alliance between the United Kingdom and Japan which had been in existence since 1902. The Japanese had built a large, modern, and highly effective fleet, as had been demonstrated as recently as the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, in which the Japanese had annihilated the Russian fleets.

War in the Pacific

When war broke out in August 1914, Japan declared war on Germany on 23rd August. Germany’s East Asia Squadron was under the command of Vice-Admiral Maximilian Reichsgraf von Spee who declined to allow his fleet to be bottled up in Tsingtao by the Japanese Navy and instead set out across the Pacific determined to do as much damage as he could to Allied territory and naval units. Japan captured the German islands north of the equator, the Marianas, the Marshalls and the Carolines, with no opposition. A largely Japanese force, though assisted by the 2nd Battalion South Wales Borderers and the 36th Sikhs, captured the base at Tsingtao on 7th November 1914 after the only major land engagement of the Far East and Pacific campaign. Whilst in possession of Tsingtao the Germans introduced their superior beer-making skills to the area and today it may be that the most visible reminder that there ever was a German Far East Empire is the excellent Tsingtao beer which comes from that region.

On 29th August 1914 the Germans on Samoa surrendered without a fight to a force of New Zealanders approximately 1,500 strong. Several days later, on 14th September, Von Spee turned up with his ships. The Franco-British Naval force had, fortunately for them,

2

withdrawn and Von Spee saw no point in retaking islands he probably could not hold in the long run, and so he departed.

The Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force, approximately 1,500 strong, landed on German New Guinea on 11th September, at Rabaul. The landing was unopposed but, when the Australians moved inland to capture the German wireless station, they encountered opposition from Melanesian police commanded by German officers. This action is known as the Battle of Bita Paka. The Australians suffered seven killed and five wounded, but by nightfall they had captured the wireless station and found that the Germans had destroyed it. The Germans had withdrawn to Toma but the Australians followed-up and laid down such a bombardment from land and naval guns that the Germans surrendered without further resistance. The first Australian battle fatality of the War was Able Seaman William George Vincent Williams, who fell in this action. He was a member of Loyal Orange Lodge 92 which met in Melbourne, and his grave is in the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery at Rabaul.

Coronel and The Falklands

Imperial Germany was a latecomer to the scramble for empire which occupied european countries in the nineteenth century and, as a result, its colonial possessions were less than those of Britain, France and Russia, and even Portugal and Belgium seemed to have greater possessions.

The Far East and the Pacific Ocean was one area where Germany was able to acquire territory and subject peoples. By the outbreak of war in 1914 Germany had the Kia Chou area of China, the north-eastern part of New Guinea and the adjacent archipelago, and islands across the Pacific, including Bougainville, Nauru, the Marshalls, the Marianas, the Carolines, and Samoa. Only Kia Chou was heavily fortified, with a port and fortress being built at Tsing Tao. The islands were lightly held, mostly by local gendarmerie with German officers.

Germany had an East Asia Squadron composed of powerful and modern warships which was intended to provide the main defence for Germany’s Pacific empire. Its main base was at Tsingtao and, on the outbreak of war the main units in the Squadron were the Armoured Cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the Light Cruisers Dresden, Emden, Leipzig and Nürnberg. The Scharnhorst had a speed of 22.5 knots while the Gneisenau was a little quicker at 23.6 knots. Armament was identical for both ships, with eight 21cm guns, six 15cm guns, eighteen 8.8cm guns, and four 45cm torpedo tubes. The light cruisers were capable of a speed around 23 knots and they each had as armament ten 10.5cm guns. Emden and Dresden each had two 50cm torpedo tubes while those on the Leipzig and Nürnberg were 45cm.

This was certainly a mighty naval force but its effectiveness was greatly reduced by the alliance between the United Kingdom and Japan which had been in existence since 1902. The Japanese had built a large, modern, and highly effective fleet, as had been demonstrated as recently as the Russo-Japanese War of 1904-5, in which the Japanese had annihilated the Russian fleets.

War in the Pacific

When war broke out in August 1914, Japan declared war on Germany on 23rd August. Germany’s East Asia Squadron was under the command of Vice-Admiral Maximilian Reichsgraf von Spee who declined to allow his fleet to be bottled up in Tsingtao by the Japanese Navy and instead set out across the Pacific determined to do as much damage as he could to Allied territory and naval units. Japan captured the German islands north of the equator, the Marianas, the Marshalls and the Carolines, with no opposition. A largely Japanese force, though assisted by the 2nd Battalion South Wales Borderers and the 36th Sikhs, captured the base at Tsingtao on 7th November 1914 after the only major land engagement of the Far East and Pacific campaign. Whilst in possession of Tsingtao the Germans introduced their superior beer-making skills to the area and today it may be that the most visible reminder that there ever was a German Far East Empire is the excellent Tsingtao beer which comes from that region.

On 29th August 1914 the Germans on Samoa surrendered without a fight to a force of New Zealanders approximately 1,500 strong. Several days later, on 14th September, Von Spee turned up with his ships. The Franco-British Naval force had, fortunately for them,

2

withdrawn and Von Spee saw no point in retaking islands he probably could not hold in the long run, and so he departed.

The Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force, approximately 1,500 strong, landed on German New Guinea on 11th September, at Rabaul. The landing was unopposed but, when the Australians moved inland to capture the German wireless station, they encountered opposition from Melanesian police commanded by German officers. This action is known as the Battle of Bita Paka. The Australians suffered seven killed and five wounded, but by nightfall they had captured the wireless station and found that the Germans had destroyed it. The Germans had withdrawn to Toma but the Australians followed-up and laid down such a bombardment from land and naval guns that the Germans surrendered without further resistance. The first Australian battle fatality of the War was Able Seaman William George Vincent Williams, who fell in this action. He was a member of Loyal Orange Lodge 92 which met in Melbourne, and his grave is in the Commonwealth War Graves Cemetery at Rabaul.

The above picture of Brother Williams is taken from the Australian War Memorial web site, http://www.awm.gov.au/ .

Brother Williams’s parents had emigrated to Australia soon after marrying in Brighton, England, in 1884. His father later died and his mother remarried. He had a sister Martha. He lived in the Northcote area of Melbourne and worked as an Engine Room Attendant at the Melbourne Electricity Supply Company. He was single. Besides being a “prominent” Orangeman he was also a member of the Richmond Rifle Club and had been in the Naval Reserve for five years when war broke out. He enlisted on 9th August 1914.

3

Brother Williams sustained a fatal wound when scouting ahead during the Australian advance on Rabaul on 11th September. He was hit in the stomach by rifle fire from Germans in a concealed position. He was taken back to HMAS Berrima where he died of his wounds. He was 28 years old.

During the capture of the German Pacific islands the Australian and New Zealand forces were defended by the battlecruiser HMAS Australia, the cruiser HMAS Melbourne and the French cruiser Montcalm. In the Grand Lodge Report of 1916 HMAS Australia is shown as having an Orange lodge on board. This is Loyal Orange Lodge 875, which is shown as “moveable”. The Worshipful Master is shown as Clarence C Crane, Yeoman of Signals, and the Secretary of the Lodge is shown as E Muldowney, PO Telegraphist, both on the Australia. In his Report that year the Grand Secretary, Rev Louis Ewart, wrote that “Great progress has already been made in numbers on the Warspite, Australia, Virginia and King Alfred.

The Emden

Von Spee having gathered his squadron together decided to attempt to make his way into the Atlantic by rounding Cape Horn. One of the light cruisers, the SMS Emden, was sent in the opposite direction, into the Indian Ocean to attack Allied shipping and generally to cause mayhem. As it happened Korvettenkapitän Karl von Müller, commanding the Emden, proved extremely able in doing exactly that. Early on the crew rigged a dummy extra funnel to make their ship look like a British cruiser.

Emden entered the Bay of Bengal on 5th September 1914 and had a very successful cruise, capturing and sinking many Allied merchantmen. On 22nd September he bombarded Madras, setting several large oil tanks ablaze and sinking another merchant ship. Before dawn on 28th October the Emden entered Penang harbour and sank the Russian cruiser Zhemchug and the French destroyer Mousquet. Müller then headed for the Cocos Islands to destroy a British wireless station and coaling facilities, reaching the islands on 9th November. The wireless station was able to send out a signal saying, “unidentified ship off entrance”, and HMAS Sydney, which was escorting an ANZAC troop convoy, set off towards the islands. The Emden put up a tremendous resistance but the Sydney had much more powerful guns and eventually pounded the German ship into submission. During her cruise Emden had sunk or captured seventeen Allied merchant ships, besides the two warships sunk at Penang, totalling 70,825 tons.

The Orange contribution in this episode was the presence of a sizeable number of brethren serving on the cruiser HMS Hampshire, which was one of the ships searching for the Emden. Emden was able to evade the Hampshire because, unknown to the British, Hampshire’s radio signals were being picked up by the Emden, giving away the British cruiser’s position.

Battle of Coronel, 1st November 1914

While Müller was causing havoc in the Indian Ocean von Spee was trying to do the same as he led his squadron across the Pacific. On 22nd September they bombarded the port of Papeete on the French island of Tahiti, sinking a gunboat. (This was the same day that the Emden had bombarded Madras and the Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy had been sunk by U-Boat

4

attack in the North Sea, so it was an inauspicious day for the Allied navies). Von Spee’s objective was to try to fight his way back home, causing as much damage as possible to Allied shipping along the way. He next headed towards the coast of Chile, where he hoped to disrupt trade routes. The British learned of his intentions through intercepted radio traffic, and Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher “Kit” Cradock was ordered to engage him.

Cradock was in command of the North America and West Indies Station. His flagship was the armoured cruiser HMS Good Hope which had a crew of 900 officers and men, a speed of 23 knots and a main armament of two 9.2-inch guns in single turrets, supplemented by sixteen 6-inch guns. He also had the armoured cruiser HMS Monmouth which had a crew of 678 officers and men, a top speed of 23 knots, and main armament of fourteen 6-inch guns. Four of these were in two twin gun turrets fore and aft with the rest in casemates amidships. HMS Otranto was also in Cradock’s squadron. Otranto was originally a liner that had been requisitioned on the outbreak of war and fitted with eight 4.7-inch guns. It had a speed of 18 knots. Cradock also had the light cruiser HMS Glasgow which had a crew of 411, a top speed of 25 knots, and a main armament of two 6-inch guns supplemented by ten 4-inch guns. The British had a good idea of the strength of Von Spee’s force and so HMS Canopus was sent to reinforce Cradock. Canopus was a pre-Dreadnought battleship which, being armed with four 12-inch guns, was a considerable addition to Cradock’s hitting power. It was an old ship, however, and had been about to be scrapped until the outbreak of war earned it a reprieve. It could manage a speed of no more than 12 knots.

Cradock felt it his duty to seek out Von Spee and left the Falklands on 22nd October, giving Canopus orders to follow on with as much speed as it could make. Glasgow had been sent forward to scout ahead of the squadron and Von Spee had assigned the same role to the Leipzig. Von Spee thought Glasgow was separated from the rest of Cradock’s squadron and moved to attack. At the same time Cradock seemed to think he had an opportunity of attacking Leipzig while it was separated from Von Spee. This brought the two squadrons into an encounter battle.

The Germans sighted the British at 16.17 while the British spotted the Germans at 16.20. Cradock turned his ships about to head south so that the two squadrons were moving roughly parallel to each other. Initially German gunnery would be affected by having to fire into the glare of the setting sun. This was an advantage Cradock sought to take. He knew the German guns had a much greater range than his, so he changed course to the south east to bring the Germans into range of his guns. Every time Cradock tried to close the range Von Spee turned away, frustrating the British attempt to get their enemy into range.

As the sun set the British ships were silhouetted against the sky, while the German ships were obscured in the darkness to the east. At 18.50 the Germans opened fire. Only the Good Hope’s two 9.2-inch guns could match the Germans for range and one of these was hit in the first five minutes. The Otranto was a large target but had only 4.7-inch guns, so it was sent away from the battle. Cradock headed straight for the enemy, desperately trying to close the range. German gunnery was remorseless and as fires started on the Good Hope and Monmouth this made them easier targets in the darkness. The Monmouth’s guns fell silent and Cradock carried on alone in the Good Hope but German fire was now concentrated on Cradock’s flagship and Good Hope’s guns fell silent at 19.50. Shortly after, the forward section blew up and the ship split apart and sank.

5

Monmouth, meanwhile, was trying to make way slowly towards the coast so that it could be beached. The German ships were searching the area for any remaining British ships, and the Nürnberg found the Monmouth. The British ship was given an opportunity to strike its colours, which it refused to do, and the Nürnberg opened fire and Monmouth sank. Both the Good Hope and the Monmouth sank with all hands. Cradock died with his men.

HMS Glasgow had been engaging the German light cruisers, and acquitting itself well, but there was no chance of it escaping destruction if it also fought the two German armoured cruisers. Glasgow ceased fire, so that it would not reveal its position by its gun flashes, and escaped south in the darkness. The British had lost two ships and 1,570 men. The Germans had suffered only three wounded.

The Germans were elated at their success and sought to make maximum propaganda capital from it. Von Spee, however, was surprisingly subdued. When presented with a bouquet of flowers he said, “These will do nicely for my grave.” He knew that his victory would spur the Royal Navy to send much stronger ships to hunt him down. He knew that the German gunnery at Coronel, which had poured streams of accurate fire onto the British ships, had consumed much of their ammunition. Scharnhorst had only 350 8.2-inch shells left, while Gneisenau had only 528.

Among those who went down with Good Hope were at least two Orange brethren, Brother A Taplin of Prince of Wales Loyal Orange Lodge 329, which was based at Portsmouth, and Brother T Hopton of Sons of William Loyal Orange Lodge 652 which, as we have seen, was based at Gillingham. Brother S W Airey, of Garston True Blues Loyal Orange Lodge 64, went down with HMS Monmouth.

Thomas Francis Hopton was born at Saint Mary De Lode in Gloucestershire on 7th July 1878, the son of Edwin and Ellen Hopton of Gloucester. He was married to Margaret and they lived at 12 Broadway, Woking, Surrey. He is described in records as a “Mechanician” and his service number was 294560. At the time of his death he was 36 years old and his name appears on Panel 3 of the Portsmouth War Memorial.

Alfred Charles Taplin was born in Portsmouth on 25th April 1882. There are records which show he enlisted in the services on 8th December 1899 and so may have seen service previous to the First World War and have gone into the Reserve when he left. Before the war he worked as a Conductor with Portsmouth Corporation Tramways, but there is also a probability that he was for a time in the Metropolitan Police. The 1911 Census has an Alfred Charles Taplin, of the same age, as a Metropolitan Police Officer living in St Pancras with a wife named Rosina and their children. There is certainly room for confusion as there were two Taplins who went down on the Good Hope. Besides our Orange Brother there was a Percy Charles Taplin who was one of the Stokers.

When Brother Taplin was recalled to the colours he was a Gunner in the Royal Marines Artillery with the Service number RMA/8564. He is commemorated on Panel 6 of the Portsmouth Naval Memorial and also on Royal Marines Memorial in the Royal Marines Museum in Portsmouth, Panel 5. His service on the Tramways is marked by his name being included on Tramways Memorial, which is now in Portsmouth Museum store.

6

The Tramways Memorial (shown below) is of such a tasteful design as would be deeply appreciated by our Orange brethren.

Brother Williams’s parents had emigrated to Australia soon after marrying in Brighton, England, in 1884. His father later died and his mother remarried. He had a sister Martha. He lived in the Northcote area of Melbourne and worked as an Engine Room Attendant at the Melbourne Electricity Supply Company. He was single. Besides being a “prominent” Orangeman he was also a member of the Richmond Rifle Club and had been in the Naval Reserve for five years when war broke out. He enlisted on 9th August 1914.

3

Brother Williams sustained a fatal wound when scouting ahead during the Australian advance on Rabaul on 11th September. He was hit in the stomach by rifle fire from Germans in a concealed position. He was taken back to HMAS Berrima where he died of his wounds. He was 28 years old.

During the capture of the German Pacific islands the Australian and New Zealand forces were defended by the battlecruiser HMAS Australia, the cruiser HMAS Melbourne and the French cruiser Montcalm. In the Grand Lodge Report of 1916 HMAS Australia is shown as having an Orange lodge on board. This is Loyal Orange Lodge 875, which is shown as “moveable”. The Worshipful Master is shown as Clarence C Crane, Yeoman of Signals, and the Secretary of the Lodge is shown as E Muldowney, PO Telegraphist, both on the Australia. In his Report that year the Grand Secretary, Rev Louis Ewart, wrote that “Great progress has already been made in numbers on the Warspite, Australia, Virginia and King Alfred.

The Emden

Von Spee having gathered his squadron together decided to attempt to make his way into the Atlantic by rounding Cape Horn. One of the light cruisers, the SMS Emden, was sent in the opposite direction, into the Indian Ocean to attack Allied shipping and generally to cause mayhem. As it happened Korvettenkapitän Karl von Müller, commanding the Emden, proved extremely able in doing exactly that. Early on the crew rigged a dummy extra funnel to make their ship look like a British cruiser.

Emden entered the Bay of Bengal on 5th September 1914 and had a very successful cruise, capturing and sinking many Allied merchantmen. On 22nd September he bombarded Madras, setting several large oil tanks ablaze and sinking another merchant ship. Before dawn on 28th October the Emden entered Penang harbour and sank the Russian cruiser Zhemchug and the French destroyer Mousquet. Müller then headed for the Cocos Islands to destroy a British wireless station and coaling facilities, reaching the islands on 9th November. The wireless station was able to send out a signal saying, “unidentified ship off entrance”, and HMAS Sydney, which was escorting an ANZAC troop convoy, set off towards the islands. The Emden put up a tremendous resistance but the Sydney had much more powerful guns and eventually pounded the German ship into submission. During her cruise Emden had sunk or captured seventeen Allied merchant ships, besides the two warships sunk at Penang, totalling 70,825 tons.

The Orange contribution in this episode was the presence of a sizeable number of brethren serving on the cruiser HMS Hampshire, which was one of the ships searching for the Emden. Emden was able to evade the Hampshire because, unknown to the British, Hampshire’s radio signals were being picked up by the Emden, giving away the British cruiser’s position.

Battle of Coronel, 1st November 1914

While Müller was causing havoc in the Indian Ocean von Spee was trying to do the same as he led his squadron across the Pacific. On 22nd September they bombarded the port of Papeete on the French island of Tahiti, sinking a gunboat. (This was the same day that the Emden had bombarded Madras and the Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy had been sunk by U-Boat

4

attack in the North Sea, so it was an inauspicious day for the Allied navies). Von Spee’s objective was to try to fight his way back home, causing as much damage as possible to Allied shipping along the way. He next headed towards the coast of Chile, where he hoped to disrupt trade routes. The British learned of his intentions through intercepted radio traffic, and Rear-Admiral Sir Christopher “Kit” Cradock was ordered to engage him.

Cradock was in command of the North America and West Indies Station. His flagship was the armoured cruiser HMS Good Hope which had a crew of 900 officers and men, a speed of 23 knots and a main armament of two 9.2-inch guns in single turrets, supplemented by sixteen 6-inch guns. He also had the armoured cruiser HMS Monmouth which had a crew of 678 officers and men, a top speed of 23 knots, and main armament of fourteen 6-inch guns. Four of these were in two twin gun turrets fore and aft with the rest in casemates amidships. HMS Otranto was also in Cradock’s squadron. Otranto was originally a liner that had been requisitioned on the outbreak of war and fitted with eight 4.7-inch guns. It had a speed of 18 knots. Cradock also had the light cruiser HMS Glasgow which had a crew of 411, a top speed of 25 knots, and a main armament of two 6-inch guns supplemented by ten 4-inch guns. The British had a good idea of the strength of Von Spee’s force and so HMS Canopus was sent to reinforce Cradock. Canopus was a pre-Dreadnought battleship which, being armed with four 12-inch guns, was a considerable addition to Cradock’s hitting power. It was an old ship, however, and had been about to be scrapped until the outbreak of war earned it a reprieve. It could manage a speed of no more than 12 knots.

Cradock felt it his duty to seek out Von Spee and left the Falklands on 22nd October, giving Canopus orders to follow on with as much speed as it could make. Glasgow had been sent forward to scout ahead of the squadron and Von Spee had assigned the same role to the Leipzig. Von Spee thought Glasgow was separated from the rest of Cradock’s squadron and moved to attack. At the same time Cradock seemed to think he had an opportunity of attacking Leipzig while it was separated from Von Spee. This brought the two squadrons into an encounter battle.

The Germans sighted the British at 16.17 while the British spotted the Germans at 16.20. Cradock turned his ships about to head south so that the two squadrons were moving roughly parallel to each other. Initially German gunnery would be affected by having to fire into the glare of the setting sun. This was an advantage Cradock sought to take. He knew the German guns had a much greater range than his, so he changed course to the south east to bring the Germans into range of his guns. Every time Cradock tried to close the range Von Spee turned away, frustrating the British attempt to get their enemy into range.

As the sun set the British ships were silhouetted against the sky, while the German ships were obscured in the darkness to the east. At 18.50 the Germans opened fire. Only the Good Hope’s two 9.2-inch guns could match the Germans for range and one of these was hit in the first five minutes. The Otranto was a large target but had only 4.7-inch guns, so it was sent away from the battle. Cradock headed straight for the enemy, desperately trying to close the range. German gunnery was remorseless and as fires started on the Good Hope and Monmouth this made them easier targets in the darkness. The Monmouth’s guns fell silent and Cradock carried on alone in the Good Hope but German fire was now concentrated on Cradock’s flagship and Good Hope’s guns fell silent at 19.50. Shortly after, the forward section blew up and the ship split apart and sank.

5

Monmouth, meanwhile, was trying to make way slowly towards the coast so that it could be beached. The German ships were searching the area for any remaining British ships, and the Nürnberg found the Monmouth. The British ship was given an opportunity to strike its colours, which it refused to do, and the Nürnberg opened fire and Monmouth sank. Both the Good Hope and the Monmouth sank with all hands. Cradock died with his men.

HMS Glasgow had been engaging the German light cruisers, and acquitting itself well, but there was no chance of it escaping destruction if it also fought the two German armoured cruisers. Glasgow ceased fire, so that it would not reveal its position by its gun flashes, and escaped south in the darkness. The British had lost two ships and 1,570 men. The Germans had suffered only three wounded.

The Germans were elated at their success and sought to make maximum propaganda capital from it. Von Spee, however, was surprisingly subdued. When presented with a bouquet of flowers he said, “These will do nicely for my grave.” He knew that his victory would spur the Royal Navy to send much stronger ships to hunt him down. He knew that the German gunnery at Coronel, which had poured streams of accurate fire onto the British ships, had consumed much of their ammunition. Scharnhorst had only 350 8.2-inch shells left, while Gneisenau had only 528.

Among those who went down with Good Hope were at least two Orange brethren, Brother A Taplin of Prince of Wales Loyal Orange Lodge 329, which was based at Portsmouth, and Brother T Hopton of Sons of William Loyal Orange Lodge 652 which, as we have seen, was based at Gillingham. Brother S W Airey, of Garston True Blues Loyal Orange Lodge 64, went down with HMS Monmouth.

Thomas Francis Hopton was born at Saint Mary De Lode in Gloucestershire on 7th July 1878, the son of Edwin and Ellen Hopton of Gloucester. He was married to Margaret and they lived at 12 Broadway, Woking, Surrey. He is described in records as a “Mechanician” and his service number was 294560. At the time of his death he was 36 years old and his name appears on Panel 3 of the Portsmouth War Memorial.

Alfred Charles Taplin was born in Portsmouth on 25th April 1882. There are records which show he enlisted in the services on 8th December 1899 and so may have seen service previous to the First World War and have gone into the Reserve when he left. Before the war he worked as a Conductor with Portsmouth Corporation Tramways, but there is also a probability that he was for a time in the Metropolitan Police. The 1911 Census has an Alfred Charles Taplin, of the same age, as a Metropolitan Police Officer living in St Pancras with a wife named Rosina and their children. There is certainly room for confusion as there were two Taplins who went down on the Good Hope. Besides our Orange Brother there was a Percy Charles Taplin who was one of the Stokers.

When Brother Taplin was recalled to the colours he was a Gunner in the Royal Marines Artillery with the Service number RMA/8564. He is commemorated on Panel 6 of the Portsmouth Naval Memorial and also on Royal Marines Memorial in the Royal Marines Museum in Portsmouth, Panel 5. His service on the Tramways is marked by his name being included on Tramways Memorial, which is now in Portsmouth Museum store.

6

The Tramways Memorial (shown below) is of such a tasteful design as would be deeply appreciated by our Orange brethren.

The picture is taken from the web site

http://www.ataleofonecity.portsmouth.gov.uk/firstworldwar/alfred-charles-taplin/

Prince of Wales Loyal Orange Lodge 329, of which Brother Taplin was a member, had met, before the War, at The Albany Hotel, Commercial Road, Landport in Portsmouth, but in the War years the Lodge met at the Thorrowgood Memorial Orange Hall on South Brighton Street in Southsea. The Lodge seems to have ceased to operate during World War Two.

South Brighton Street seems to have disappeared from maps of Portsmouth, demolished either by modernisers or the Luftwaffe. The “Orange Memorial Hall” there is shown in the 1915 Lodge Directory. In 1916 and 1919 it had been renamed the Thorrowgood Memorial Orange Hall. The name Thorrowgood may refer to Samuel Charles Thorrowgood, a native of Portsmouth born on 28th July 1876 and son of Samuel Isaac Hosier Thorrowgood and Sarah Ann. His father was a Gunner’s Mate in the Royal Navy. Young Samuel lied about his age

7

and joined the Royal Navy on 13th July 1894. He took part in the Benin Campaign in 1897 and on 12th January 1902 he married Annie Elizabeth Wooden at the Lake Road Baptist Church. They went to live at 52 Moorland Road, Portsmouth. Through all this time he was still serving in the Royal Navy and on 4th September 1913 he was transferred to the battlecruiser HMS Queen Mary. He fought at the battles of Heligoland Bight and the Dogger Bank. The Queen Mary took part in the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916 and he was one of those who died when the ship was sunk. He is commemorated on Panel 20 of the Portsmouth War Memorial. We do not know at the time of writing that the Thorrowgood after whom the Hall was named was Samuel Charles Thorrowgood, and we do not know if he was an Orangeman, but the weight of evidence suggests he probably was.

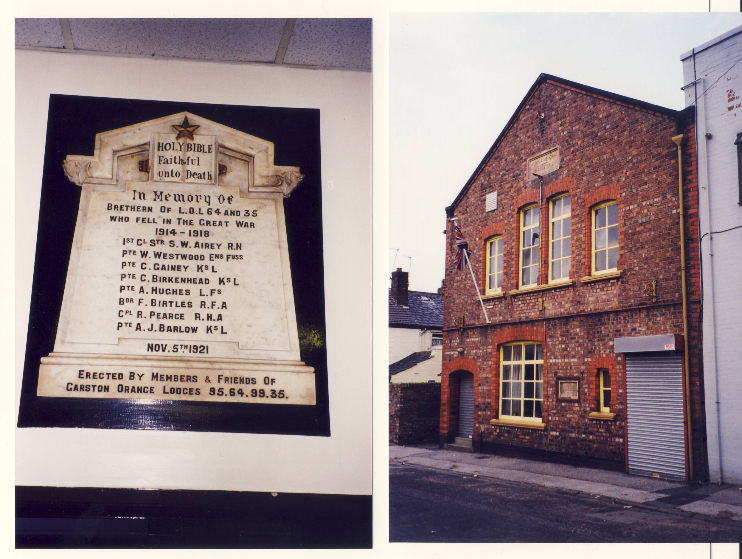

Sam Winn Airey was the Orange brother who went down with the Monmouth. He had been born on 7th August 1892 and was the son of John and Margaret E Airey of 8 Dock Road, Garston, which was in the process of becoming part of the city of Liverpool. Sam was a Stoker 1st Class and his service number was SS/110698. He is commemorated on Panel 3 of the Plymouth Naval Memorial and also on the World War I Memorial in St Michael’s Church, Garston, where he was a parishioner. Being a member of Garston True Blues Loyal Orange Lodge number 64, he is also commemorated on the War Memorial in the Victoria Memorial Orange Hall on Heald Street in Garston.

http://www.ataleofonecity.portsmouth.gov.uk/firstworldwar/alfred-charles-taplin/

Prince of Wales Loyal Orange Lodge 329, of which Brother Taplin was a member, had met, before the War, at The Albany Hotel, Commercial Road, Landport in Portsmouth, but in the War years the Lodge met at the Thorrowgood Memorial Orange Hall on South Brighton Street in Southsea. The Lodge seems to have ceased to operate during World War Two.

South Brighton Street seems to have disappeared from maps of Portsmouth, demolished either by modernisers or the Luftwaffe. The “Orange Memorial Hall” there is shown in the 1915 Lodge Directory. In 1916 and 1919 it had been renamed the Thorrowgood Memorial Orange Hall. The name Thorrowgood may refer to Samuel Charles Thorrowgood, a native of Portsmouth born on 28th July 1876 and son of Samuel Isaac Hosier Thorrowgood and Sarah Ann. His father was a Gunner’s Mate in the Royal Navy. Young Samuel lied about his age

7

and joined the Royal Navy on 13th July 1894. He took part in the Benin Campaign in 1897 and on 12th January 1902 he married Annie Elizabeth Wooden at the Lake Road Baptist Church. They went to live at 52 Moorland Road, Portsmouth. Through all this time he was still serving in the Royal Navy and on 4th September 1913 he was transferred to the battlecruiser HMS Queen Mary. He fought at the battles of Heligoland Bight and the Dogger Bank. The Queen Mary took part in the Battle of Jutland on 31st May 1916 and he was one of those who died when the ship was sunk. He is commemorated on Panel 20 of the Portsmouth War Memorial. We do not know at the time of writing that the Thorrowgood after whom the Hall was named was Samuel Charles Thorrowgood, and we do not know if he was an Orangeman, but the weight of evidence suggests he probably was.

Sam Winn Airey was the Orange brother who went down with the Monmouth. He had been born on 7th August 1892 and was the son of John and Margaret E Airey of 8 Dock Road, Garston, which was in the process of becoming part of the city of Liverpool. Sam was a Stoker 1st Class and his service number was SS/110698. He is commemorated on Panel 3 of the Plymouth Naval Memorial and also on the World War I Memorial in St Michael’s Church, Garston, where he was a parishioner. Being a member of Garston True Blues Loyal Orange Lodge number 64, he is also commemorated on the War Memorial in the Victoria Memorial Orange Hall on Heald Street in Garston.

(Left: the War Memorial in Garston Orange Hall, Right: Garston Orange Hall from the outside.)

8

The Battle of the Falkland Islands, 8th December 1914

We have seen how Von Spee thought that his destruction of Cradock’s force would goad the British into hunting him down, to which end they would commit ships large enough to be capable of overwhelming his force. His assessment was exactly right.

Rear-Admiral Archibald Stoddart was already in the south Atlantic with the armoured cruisers HMS Carnarvon and HMS Cornwall. In addition the armoured cruisers HMS Defence and HMS Kent were on their way to join him. Returning from the defeat at Coronel, HMS Canopus and HMS Glasgow arrived at Port Stanley in the Falklands. Canopus was virtually immobile but still had its four 12-inch guns. It was decided to anchor the ship in Stanley harboured to be used as a defence battery.

Most importantly the Admiralty despatched two battlecruisers, HMS Invincible and HMS Inflexible, to the south Atlantic under the command of Vice-Admiral Doveton Sturdee. Each battlecruiser had eight 12-inch guns in four twin turrets, meaning that Von Spee would be massively outgunned if the two forces came to battle. Sturdee’s force came together at Port Stanley on 7th December where the light cruiser HMS Bristol and the armed merchant cruiser HMS Macedonia had arrived the day before.

Von Spee was unaware of this concentration of British naval power and decided to attack British installations at Port Stanley, arriving there on the morning of 8th December. As Spee approached Stanley he was surprised to come under fire from an unknown source, which was Canopus’s 12-inch guns, firing from its position in Stanley Harbour. German lookouts also reported that they had sighted the distinctive tripod masts of British battlecruisers. Von Spee turned his ships about and headed away, but he already knew he was doomed.

The British had also been surprised because they were not expecting Spee to show up. The British ships were coaling and the crews were having breakfast. Historians have speculated that, had Von Spee charged headlong at the British fleet it would have been caught at anchor. Perhaps if a ship had been sunk in the harbour the rest of the fleet would have been unable to set to sea.

These are the “what-ifs” of history. What happened is that Von Spee took his fleet away with all the speed he could muster. The British calmly finished their breakfasts, knowing that they had the sped to catch him. The British left harbour at 10.00 and caught up with Von Spee three hours later. The battlecruisers opened fire at 13.00 and Von Spee engaged them with the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, hoping to give the German light cruisers a chance to escape. The battle was an unequal one, though German seamanship enabled them to last for several hours. Scharnhorst sank at 16.17 and Gneisenau’s crew abandoned her and she sank at 18.02.

HMS Kent chased down the Nürnberg which sank at 19.27. Glasgow and Cornwall chased down the Leipzig and brought it to battle. Leipzig ran out of ammunition and could no longer fight. Two flares were fired and the British ceased fire to accept the Leipzig’s surrender, but the German light cruiser was so badly damaged that it rolled over and sank at 21.23. Glasgow had survived the Battle of Coronel and had been in at the kill at the Battle of the Falkland Islands. There must have been a sense of satisfaction at having avenged their fallen comrades from Cradock’s squadron. Von Spee had died in the battle, as had two of his sons.

9

The Last Act

Of Von Spee’s force the only two ships to survive the Battle of the Falkland Islands was the light cruiser Dresden and the auxiliary Seydlitz. The Seydlitz was soon interned.

The Dresden returned to the Pacific and stayed close to the coast of Chile for a few months. British ships were out looking for her and on 14th March 1915 they found her, in Cumberland Bay near the island of Más a Tierra. The British cruisers HMS Kent and HMS Glasgow were the ones who had found her. The Dresden’s Captain did not think his ship was in any position to offer resistance and scuttled his ship after a brief exchange of fire with the Glasgow. Von Spee’s squadron had now been wiped out and presented no further threat to the Allies. The crew of the Glasgow must have taken special pleasure in this, having seen the loss of their mates on Good Hope and Monmouth at Coronel.

The Orange contribution

The Orangemen were also in a position to derive satisfaction from the fact that they had avenged their fallen comrades at the Coronel. Among ships that took part in the hunting and destruction of Von Spee were HMS Carnarvon; HMS Defence; and HMS Inflexible. Each of these ships had Orangemen in their crew.

HMS Defence had taken part in the unsuccessful attempt to engage the Goeben and the Breslau in the Mediterranean during the opening days of the War. Defence was ordered to reinforce Cradock’s squadron on 10th September 1914 but the order was countermanded. In October Defence was once again ordered to reinforce Cradock, but had got only as far as the southern Atlantic by the time Cradock had been defeated at Coronel. Defence then waited in the area long enough to rendezvous with HMS Invincible and transferred long-range radio equipment to the battlecruiser. After that she was ordered to South Africa to escort a troop convoy, and so was denied the opportunity to be in at the kill.

HMS Carnarvon took part in the Battle of the Falkland Islands. At the time the ship could make no more than 18 knots, which meant it did not have the speed to join with the other British cruisers in overtaking and sinking their German opposite numbers. Instead, Carnarvon gave support to the British battlecruisers that took on and sank the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. For a time the ship took part in the hunt for the Dresden but was eventually ordered north to Brazil.

HMS Inflexible was also one of the ships that had failed to interdict the Goeben and the Breslau, but was one of the battlecruisers that ensured the destruction of Von Spee. The crewmen of all these three ships who can be recognised as Orangemen were members of “Carnarvon” Loyal Orange Lodge number 827. This lodge was originally composed of crew members of HMS Carnarvon but at the outbreak of the War some must have been posted to other ships.

Before closing it is worth remembering again the Orangemen who served aboard HMAS Australia. That ship’s eight 12-inch guns caused Von Spee to give the ship a wide berth, and Australia effectively guarded large parts of the Pacific from German attack. Rear-Admiral George Patey, whose flagship Australia was, had correctly deduced that Von Spee would make for South America and wanted to be after him. His orders, however, were to guard

10

areas further west. After the defeat at Coronel, Patey and the Australia were made the centrepiece of a multi-national naval force that went in search of Von Spee. This time the orders were to block Von Spee from any move north and guard the Panama Canal. When news came of the destruction of Von Spee and his squadron Patey and his entire crew, including no doubt his Orangemen, were disappointed not to have had a crack at the Germans.

Michael Phelan

Historian

Grand Orange Lodge of England

18th July 2014

The Battle of the Falkland Islands, 8th December 1914

We have seen how Von Spee thought that his destruction of Cradock’s force would goad the British into hunting him down, to which end they would commit ships large enough to be capable of overwhelming his force. His assessment was exactly right.

Rear-Admiral Archibald Stoddart was already in the south Atlantic with the armoured cruisers HMS Carnarvon and HMS Cornwall. In addition the armoured cruisers HMS Defence and HMS Kent were on their way to join him. Returning from the defeat at Coronel, HMS Canopus and HMS Glasgow arrived at Port Stanley in the Falklands. Canopus was virtually immobile but still had its four 12-inch guns. It was decided to anchor the ship in Stanley harboured to be used as a defence battery.

Most importantly the Admiralty despatched two battlecruisers, HMS Invincible and HMS Inflexible, to the south Atlantic under the command of Vice-Admiral Doveton Sturdee. Each battlecruiser had eight 12-inch guns in four twin turrets, meaning that Von Spee would be massively outgunned if the two forces came to battle. Sturdee’s force came together at Port Stanley on 7th December where the light cruiser HMS Bristol and the armed merchant cruiser HMS Macedonia had arrived the day before.

Von Spee was unaware of this concentration of British naval power and decided to attack British installations at Port Stanley, arriving there on the morning of 8th December. As Spee approached Stanley he was surprised to come under fire from an unknown source, which was Canopus’s 12-inch guns, firing from its position in Stanley Harbour. German lookouts also reported that they had sighted the distinctive tripod masts of British battlecruisers. Von Spee turned his ships about and headed away, but he already knew he was doomed.

The British had also been surprised because they were not expecting Spee to show up. The British ships were coaling and the crews were having breakfast. Historians have speculated that, had Von Spee charged headlong at the British fleet it would have been caught at anchor. Perhaps if a ship had been sunk in the harbour the rest of the fleet would have been unable to set to sea.

These are the “what-ifs” of history. What happened is that Von Spee took his fleet away with all the speed he could muster. The British calmly finished their breakfasts, knowing that they had the sped to catch him. The British left harbour at 10.00 and caught up with Von Spee three hours later. The battlecruisers opened fire at 13.00 and Von Spee engaged them with the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, hoping to give the German light cruisers a chance to escape. The battle was an unequal one, though German seamanship enabled them to last for several hours. Scharnhorst sank at 16.17 and Gneisenau’s crew abandoned her and she sank at 18.02.

HMS Kent chased down the Nürnberg which sank at 19.27. Glasgow and Cornwall chased down the Leipzig and brought it to battle. Leipzig ran out of ammunition and could no longer fight. Two flares were fired and the British ceased fire to accept the Leipzig’s surrender, but the German light cruiser was so badly damaged that it rolled over and sank at 21.23. Glasgow had survived the Battle of Coronel and had been in at the kill at the Battle of the Falkland Islands. There must have been a sense of satisfaction at having avenged their fallen comrades from Cradock’s squadron. Von Spee had died in the battle, as had two of his sons.

9

The Last Act

Of Von Spee’s force the only two ships to survive the Battle of the Falkland Islands was the light cruiser Dresden and the auxiliary Seydlitz. The Seydlitz was soon interned.

The Dresden returned to the Pacific and stayed close to the coast of Chile for a few months. British ships were out looking for her and on 14th March 1915 they found her, in Cumberland Bay near the island of Más a Tierra. The British cruisers HMS Kent and HMS Glasgow were the ones who had found her. The Dresden’s Captain did not think his ship was in any position to offer resistance and scuttled his ship after a brief exchange of fire with the Glasgow. Von Spee’s squadron had now been wiped out and presented no further threat to the Allies. The crew of the Glasgow must have taken special pleasure in this, having seen the loss of their mates on Good Hope and Monmouth at Coronel.

The Orange contribution

The Orangemen were also in a position to derive satisfaction from the fact that they had avenged their fallen comrades at the Coronel. Among ships that took part in the hunting and destruction of Von Spee were HMS Carnarvon; HMS Defence; and HMS Inflexible. Each of these ships had Orangemen in their crew.

HMS Defence had taken part in the unsuccessful attempt to engage the Goeben and the Breslau in the Mediterranean during the opening days of the War. Defence was ordered to reinforce Cradock’s squadron on 10th September 1914 but the order was countermanded. In October Defence was once again ordered to reinforce Cradock, but had got only as far as the southern Atlantic by the time Cradock had been defeated at Coronel. Defence then waited in the area long enough to rendezvous with HMS Invincible and transferred long-range radio equipment to the battlecruiser. After that she was ordered to South Africa to escort a troop convoy, and so was denied the opportunity to be in at the kill.

HMS Carnarvon took part in the Battle of the Falkland Islands. At the time the ship could make no more than 18 knots, which meant it did not have the speed to join with the other British cruisers in overtaking and sinking their German opposite numbers. Instead, Carnarvon gave support to the British battlecruisers that took on and sank the Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. For a time the ship took part in the hunt for the Dresden but was eventually ordered north to Brazil.

HMS Inflexible was also one of the ships that had failed to interdict the Goeben and the Breslau, but was one of the battlecruisers that ensured the destruction of Von Spee. The crewmen of all these three ships who can be recognised as Orangemen were members of “Carnarvon” Loyal Orange Lodge number 827. This lodge was originally composed of crew members of HMS Carnarvon but at the outbreak of the War some must have been posted to other ships.

Before closing it is worth remembering again the Orangemen who served aboard HMAS Australia. That ship’s eight 12-inch guns caused Von Spee to give the ship a wide berth, and Australia effectively guarded large parts of the Pacific from German attack. Rear-Admiral George Patey, whose flagship Australia was, had correctly deduced that Von Spee would make for South America and wanted to be after him. His orders, however, were to guard

10

areas further west. After the defeat at Coronel, Patey and the Australia were made the centrepiece of a multi-national naval force that went in search of Von Spee. This time the orders were to block Von Spee from any move north and guard the Panama Canal. When news came of the destruction of Von Spee and his squadron Patey and his entire crew, including no doubt his Orangemen, were disappointed not to have had a crack at the Germans.

Michael Phelan

Historian

Grand Orange Lodge of England

18th July 2014